For years, amberbatts.com has been a space where I’ve shared my thoughts, experiences, and advocacy work. But meaningful conversations don’t happen in isolation – they grow through different perspectives, insights, and lived experiences.

That’s why I’m introducing a guest commentary. From time to time, I’ll be inviting others to share their perspectives here, adding new layers to the conversations we’re already having. These voices may offer analysis, personal stories, or critical discussions on the issues that matter.

Do you want to write something and have it posted here? Reach out.

I’m excited to kick things off with Dave Stephenson.

Dave is a disabled Tlingit veteran from Juneau, Alaska. He was stationed in the DC area and Alaska. He is a freelance journalist and has a bachelor’s degree in journalism from Fort Lewis College in Colorado, where he graduated magna cum laude.

I’m an Alaska Native army veteran who, rather ironically, was stationed at Fort Wainwright, in Fairbanks Alaska. This is ironic because soldiers rarely awarded their station of choice from their “dream sheet.”

Long before arriving at Wainwright, when I was still in basic training, I was exposed to the rampant anti-Native racism rife in the U.S. military. I was ordered to sing cadences – marching songs – that reference Alaska Native women’s genitals as being “mighty cold,” told that enemy territory is “Indian country,” the enemy is “Indians” and “savages,” and that Native American names and words were white property, and could be used as ironic nicknames, platoon names and as equipment and weapons nomenclature.

When my group of soldiers arrived at Fort Wainwright, my new company commander cautioned us about visiting downtown Fairbanks, because local “Eskimos” would beat and rob us, possibly even murder us.

We were quickly reminded that as Arctic soldiers we had to demonstrate our toughness by “raping squaws and wrassling polar bears.”

My aunt and female cousins lived just down Richardson Highway from Wainwright. When the other soldiers laughed, my outrage, alienation, and disillusionment only increased.

It is this language and attitude on the part of the U.S. military that has directly contributed to the history of white military men’s habitual rapes of Native women and white society’s tolerance and endorsement of the rapes and murders.

As recently as 2018, Alaska courts gave a white man a “rape pass” seemingly continuing to allow the victimization of Native women with impunity.

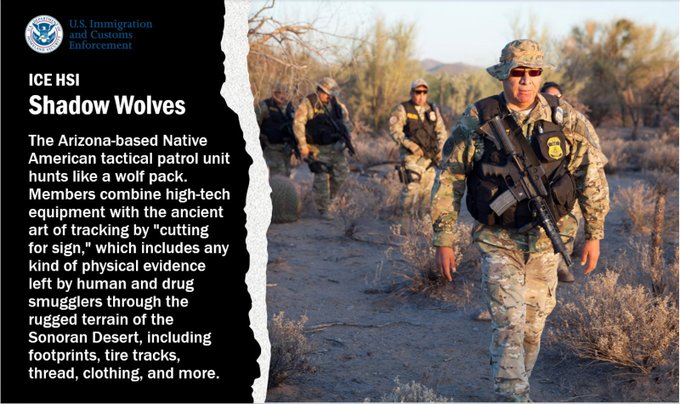

Shadow Wolves are @DHSgov’s only #NativeAmerican tracking unit, combining high-tech gear and the ancient art of tracking.

Although American Indians and Alaska Natives serve in the Armed Forces at five times the national average, Donald Trump’s newly appointed Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth recently abolished Native American Heritage Month in the military.

If you’re an Alaska Native or Native American, carefully consider the implications before enlisting in institutions that demean your identity, treat your people as enemies, and fuel the ongoing crisis of violence against Native women. The military’s decision to cancel Native American Heritage Month is more than just an oversight – it is part of a broader effort to erase Indigenous history, silence Native voices, and uphold a system that marginalizes and disregards Native contributions. This deliberate act of erasure makes it clear that while Native people are expected to serve, their history and sacrifices are not worthy of recognition.

Trump’s attempt to overturn birthright citizenship in an executive order uses an 1884 Native American case, Elk v. Wilkins as a legal analogy. The implications of applying the logic of Elk v. Wilkins today would mean that the U.S. government could deny Native Americans the rights and privileges of U.S. citizenship.

Trump issued an executive order that would eliminate birthright citizenship, but a federal judge blocked the order temporarily shortly after 22 states quickly mounted a legal challenge.

There are alarming reports of ICE agents detaining and harassing Native Americans. Reports of ICE agents detaining and harassing Native Americans have raised serious concerns about racial profiling, violations of sovereignty, and the erosion of Indigenous rights. In some cases, Native people, particularly those living near the U.S.-Canada and U.S.-Mexico borders, have been stopped, questioned, and even detained despite carrying valid tribal IDs or proof of citizenship. Tribes nationwide are rushing to provide IDs, legal protection, and information as ICE increasingly stops Native Americans, demanding proof of citizenship.

In Southeast Alaska, Tlingit and Haida, a tribal government representing over 37,000 Tlingit and Haida Alaska Natives worldwide, responded to Executive Orders from the Trump Administration by sharing how and where to get a tribal ID and a summary of the potential impacts on Tlingit & Haida and Southeast Alaska Native communities which included a pause in the funding of energy and infrastructure; protection of access to our traditional lands and resources.

The U.S. military has long relied on the service of Native Americans, yet it continues to uphold the very structures of racism, violence, and erasure that have historically oppressed Indigenous people.

The Native post-colonial scholar and thinker Eduardo Duran says that the U.S. military is no place for Native Americans, and given the prevailing attitudes and additional traumas Natives experience in the military, he’s probably right.

The decision to abolish Native American Heritage Month in the military is nothing short of a slap in the face to the thousands of Native soldiers who have fought and died for a country that still refuses to respect them. It sends a clear message: Native contributions are good enough for war, but not worthy of recognition. This erasure, combined with the military’s entrenched racism and its long history of enabling violence against Native communities, makes it painfully clear that Indigenous service members are expected to give everything while receiving little in return.

Until these injustices are confronted, Alaskan Natives and Native Americans must ask themselves – why should we continue to serve an institution that refuses to honor us?

Read more from Dave Stephenson here.

Leave a comment