Refuge definition: shelter or protection from danger or distress; a place that provides shelter or protection; something to which one has recourse in difficulty.

But Refuge Coffee Collaboration, backed by Priceless Alaska, offers no such refuge to sex trafficking victims and sex workers who do not meet their redeemable victim criteria (i.e., someone who opposes laws that harm sex trafficking survivors and sex workers).

Refuge Coffee Collaboration recently opened its doors in the Spenard neighborhood of Anchorage, presenting itself as a warm and welcoming café “supporting survivors of human trafficking”. Refuge claims that proceeds go toward helping survivors.

THE BACK STORY

Dicey Pricey – The Tale of Priceless details how a spacious South Anchorage home, donated to house trafficking victims, sat mostly empty. Despite the public image of tireless aid and outreach, few sex trafficking survivors found shelter behind its doors. Serious questions arose about how funds were used and who was actually being served.

Now, with Refuge Coffee Collaboration opening, those questions continue to go unanswered.

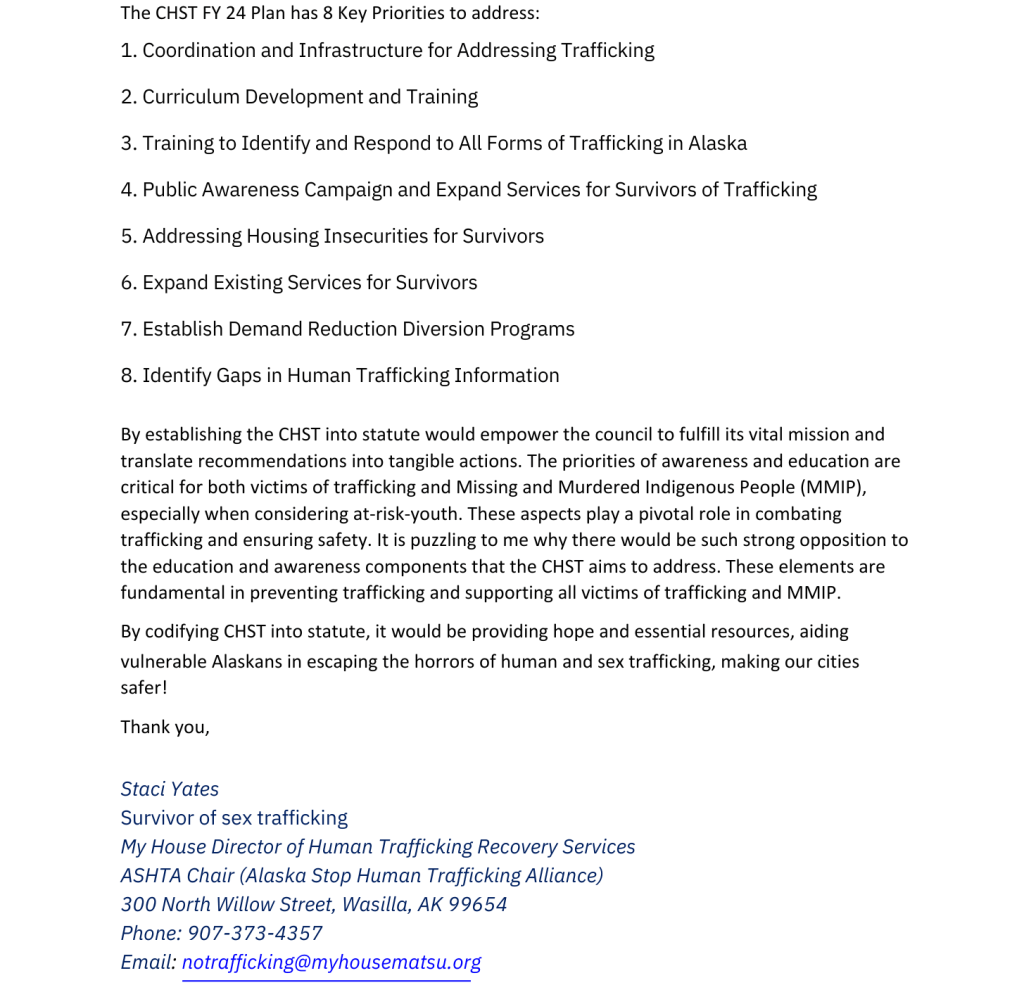

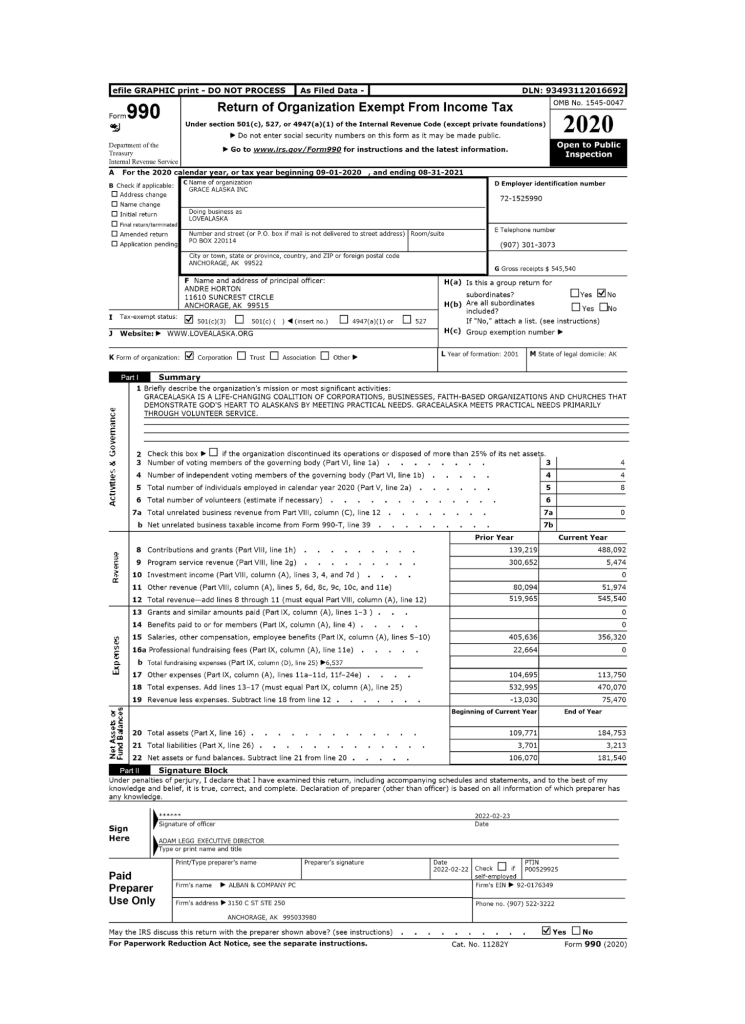

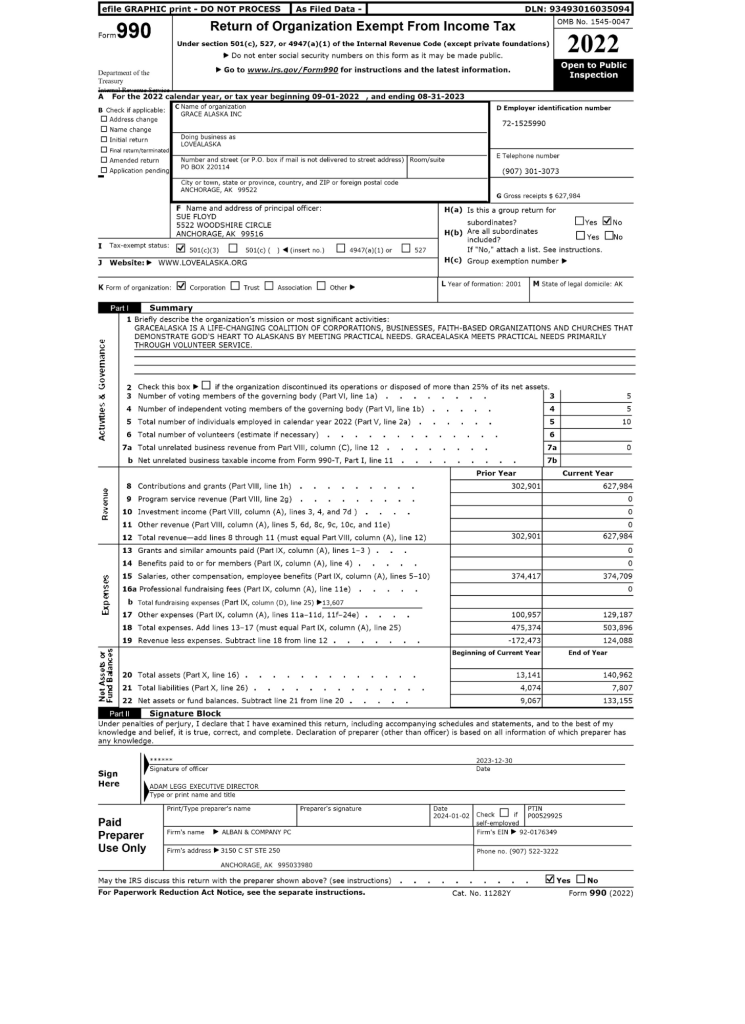

A simple look into the organization’s EIN (72-1525990) reveals the multiple religious based nonprofits operating under the umbrella Grace Alaska: Love Alaska, Priceless Alaska, Chosen Alaska.

Love Alaska markets itself as a nonprofit aiming to uplift Alaskans by encouraging volunteer involvement in “hurting areas of society.” On the surface, this sounds noble. But a closer look reveals vague claims and a lack of clarity about how donations are actually used. Through its initiatives, Priceless and Chosen, the organization trains mentors to engage with trafficking survivors and at-risk youth. However, their language deliberately blurs the line between consensual sex work and sex trafficking, a conflation that fuels dangerous policies and public misunderstandings.

These groups use similar language about serving the marginalized, but their actions tell another story.

Instead of offering direct services to survivors, much of their effort appears focused on training volunteers, including law enforcement and the general public to “spot trafficking.” This approach centers outsiders and institutions rather than empowering those with lived experience. It also reinforces harmful stereotypes, excluding actual sex workers from the conversation unless they fit a narrow “rescued victim” narrative.

We are either the right kind of religious victim or we are pimps because we do not buy into their shame and fear-based religious stance.” – Anonymous sex worker who had previously been provided services from Priceless.

NOW OPEN

Refuge Coffee Collaboration, owned by Grace Alaska per their business license, is open for business in Spenard, a neighborhood named after the colorful French-Canadian, Joe Spenard. Much like the man himself, Spenard has historically been known for its independence and notoriety for a good time, with working houses in a quasi red-light district up until the early 2000’s, rowdy bars and one of the only strip clubs that actually paid it’s dancers an hourly wage. RIP PJ’s.

Spenard was it’s own city until September 1975.

Refuge was recently featured in the Anchorage Daily News’ Open & Shut series, which tracks business openings and closings, noting that the café provides jobs for sex trafficking survivors, “We don’t put them on the bar, but they help pick out items for merchandise and help with food preparation,” said Allison Mogensen, the current executive director of Priceless and previous Director of Client Care at Love Alaska, “It’s back-of-house work for their safety and our safety.”

Morgensen stepped into the role of Executive Director for Priceless in September 2023. Before that, she worked with both Priceless and Chosen, first as a Case Manager (2021–2022) and then as Director of Client Care (2022–2023). In public appearances, she frequently references an FBI award as a mark of the organization’s credibility, describing it as recent, though it was actually given in 2018. The continued emphasis on a seven-year-old award raises questions about the organization’s more current accomplishments.

On the back wall, behind a long table designed for group gatherings, are black-and-white images of several Alaska sex trafficking survivors whom Priceless claims to have served. Small placards highlight their individual stories, images muted in black and white with gold accents covering their faces so their identities aren’t distinguishable.

One portrait of TL, a sex trafficking survivor, shared that Priceless got her story wrong. TL shared she had asked Priceless years ago to change her bio, yet they had not, “I wasn’t a meth user. I asked them to change it. It never was changed.”

DARING TO SPEAK OUT

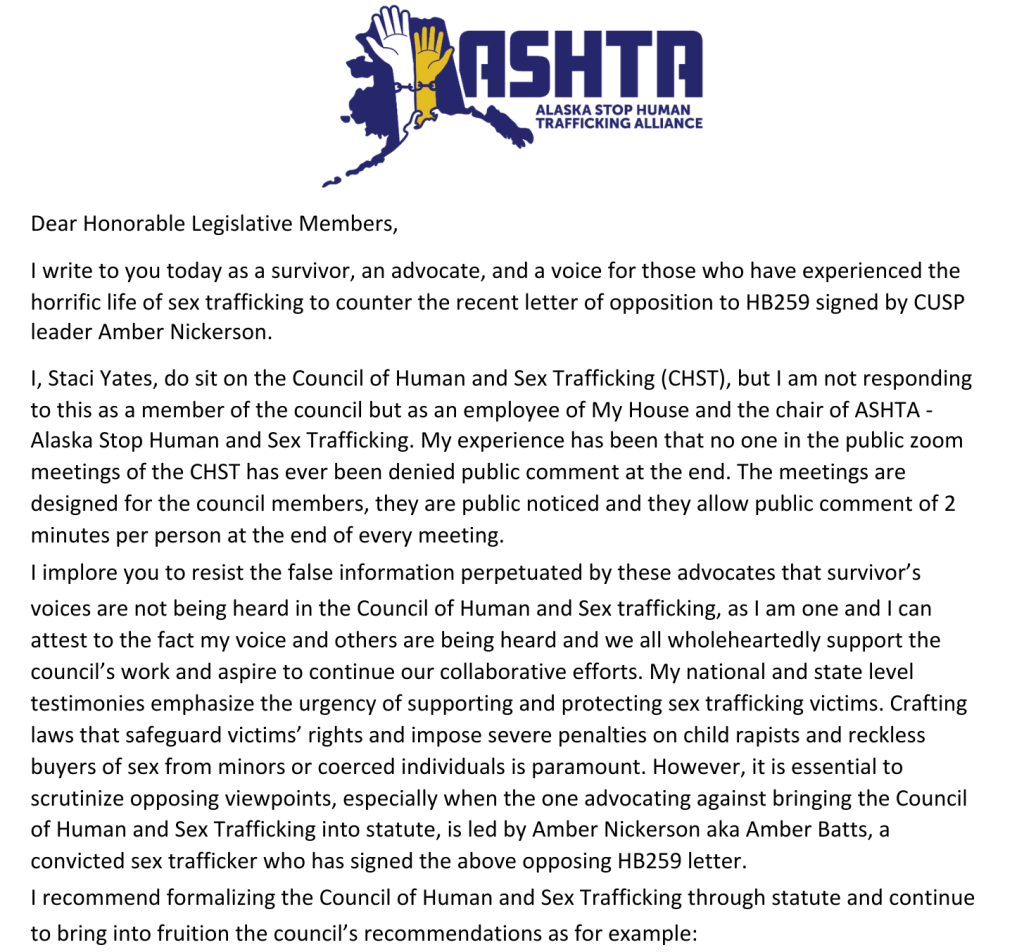

Some sex trafficking survivors and sex workers from Community United for Safety and Protection have dared to speak out against proposed laws that would further harm their communities. While they advocate for safety, rights, and harm reduction, organizations like MyHouse, Priceless, and the Alaska Stop Human Trafficking Alliance (ASHTA) work closely together to lobby lawmakers and influence legislation without involving or listening to the people most directly affected. Survivors and sex workers who challenge these efforts or offer alternative perspectives are frequently discredited, sometimes even labeled as “pimps” or “traffickers,” especially when their advocacy conflicts with the narratives and goals promoted by these well-funded, politically connected organizations.

There’s little room in the narrative for empowered sex trafficking survivors or sex workers, those who survived without being “saved.” People who speak out against harmful policies are often vilified, especially if they don’t fit the narrow image of a redeemable victim.

“The heart of the coffee shop is creating space for the community to learn more about trafficking in our state,” Morgensen said in the Anchorage Daily News series.

But whose stories are actually welcome in that space, and whose stories are left out?

FOLLOW THE MONEY

The IRS Form 990 is a public document that nonprofits must file each year. It shows how they make and spend money. Anyone can look it up online to see how nonprofits are using their funds.

In 2020 Grace Alaska received over $51,974 in for the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act Grant.

Raising money using the image of helpless girls chained in basements and rather than funding shelter or harm reduction, the money donated supports business ventures centered on more fundraising.

Meanwhile, Priceless mentors are enlisted to spread religious rhetoric under the guise of fighting sex trafficking. The founder and executive director of Priceless, Gwen Adams (a self-proclaimed crazy church lady), sits on committees and holds leadership roles that inform legislative policies of prostitution laws.

In 2020, Priceless reported $5,474 in “program service revenue,” categorized as “class fees.” It appears they’re charging mentors and offering paid “sex trafficking awareness” classes, raising the question: If the goal is to support survivors, why is the focus on monetizing training instead of providing real, accessible services?

In 2022, they received more than $178,000 in grants. The 2022 990 lists a grant from the Alaska Native Women’s Resource for survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault from cultural specific populations. However, it does not specify how much of the $178,049 in total government grant revenue came from that source, raising concerns about transparency in how public funds are tracked and reported.

HOUSE BILL 68

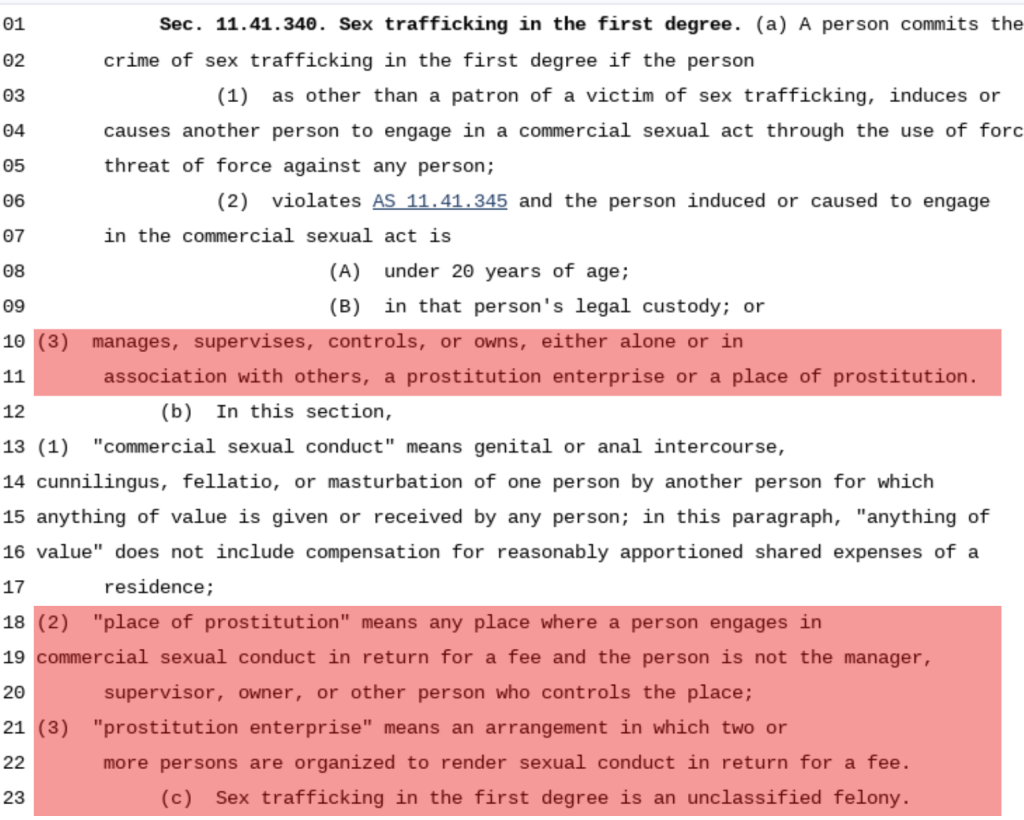

House Bill 68, introduced in the Alaska legislative 2023/2024 session, proposed a new Class B felony: Prostitution in the First Degree.

This statute change would have criminalized owning, supervising, or managing a place where someone engages in sex for a fee.

Earlier drafts defined a prostitution enterprise as two or more people organized to exchange sexual conduct for money. The bill aimed to target traffickers by reducing demand through criminalizing those who purchase sex, and created harsher penalties for consensual sex workers working together for safety.

Gwen Adams, the founder and current executive director of Priceless at the time, fully supported House Bill 68, although it would have made having a place of prostitution Sex Trafficking in the First Degree, an unclassified felony.

In Alaska, unclassified felonies, like murder or sexual assault, have set sentences written into law ranging from 30 to 99 years in prison.

Adams gave an emotionally charged presentation in support of House Bill 68, citing numbers and data without offering any sources or explaining where the information came from.

The full presentation from Priceless had data without citing where the numbers came from.

Still, HB 68 had some good parts, like the vacation of judgment for prostitution and misconduct involving a controlled substance if the person was a victim of sex trafficking, although there was some confusion about how a person would have to prove they were a sex trafficking victim.

In a subsequent draft of HB 68, it lists presumption and burden of proof in a vacation of judgment, “must prove all factual assertions by a preponderance of the evidence.“

Overall, HB 68 sought to expand criminal penalties while doing nothing to protect sex trafficking survivors or sex workers and would have expanded laws increasing police power, encourage profiling, while making it more dangerous for people in the sex trade to access safety, housing, or justice.

In what world does arresting sex trafficking survivors and sex workers for felonies combat sex trafficking? The founder of Priceless is lobbying for laws that criminalize the very people they claim to raise money and get grants to protect.

Right now, in Alaska, prostitution is a Class B misdemeanor, which is up to 90 days in jail and a fine of $2000.

MOVING FORWARD

The newly opened café in Anchorage’s Spenard neighborhood presents itself as a community-oriented space supporting survivors of human trafficking.

In an Instagram post from in January earlier this year, National Human Trafficking Awareness month, both Adam Legg, the Executive Director at Love Alaska, and Morgensen talk about the injustice of enslavement, with “all of us in the community being involved in that fight”.

Refuge states that proceeds go into programs to assist individuals affected by trafficking.

But do they?

If Refuge Coffee Collaboration is to be a true refuge, it must start by listening to the people it claims to serve. It must make space for sex trafficking survivors and sex workers at the table. Not as tokens for grants, not as warnings, but as equals.

Until then, there is no refuge here.

Leave a comment