How Self-Defense Claims Collide with Reality in Alaska Courts

Roughly 360 miles apart, the cases of Tessa Hillyer and Luke Charles Simonson are linked by the same legal question: does Alaska’s self-defense law justify deadly force here, or not?

One case centers on an alleged sexual assault at a Fairbanks campground. The other follows a shooting after a youth soccer practice in a crowded Anchorage parking lot.

A Duke Law review, SURVEY OF ALASKA’S LAW OF SELF-DEFENSE, underscores a key issue in the Anchorage case: if a defendant moves toward the person they later shoot, that can become a legal disqualifier for self-defense, regardless of the defendant’s claimed fear.

Anchorage: The Fox Hollow Case

The Anchorage case stems from November 8, 2025, outside the Fox Hollow Golf Course & Sports Dome. Luke Charles Simonson, 36, is charged with first- and second-degree murder in the death of Timothy Grosdidier, 45. According to charging documents, the conflict began after Simonson nearly struck a child with his truck. Simonson told investigators that Grosdidier was unarmed but yelling and “kept advancing,” and that Simonson feared for his safety.

Prosecutors say dashcam video contradicts Simonson’s account, showing him stepping out with his gun already drawn, moving toward Grosdidier, and firing as Grosdidier does not appear to advance. They argue that “moving toward” is legally significant: the Duke review notes self-defense protects someone under attack, not someone who escalates a dispute they helped provoke.

Fairbanks: A Self-Defense Claim After an Alleged Sexual Assault

Simonson’s case is still pretrial, but Tessa Hillyer, 38, has already been tried for the May 2025 shooting death of Raymond M. McPherson Jr., 48, at a Fairbanks campground, where he was found with six gunshot wounds. The trial focused on whether her use of force was justified and proportional, and what jurors could hear about the victim.

Prosecutors said Hillyer reported an attempted sexual assault and claimed self-defense, investigators noting a bruise near her eye. At trial, she testified that McPherson tried to force sexual contact, hit her, and that she shot him only after escaping to her car, grabbing her pistol, and firing as he lunged until the magazine was empty.

Bail and the Question of Who Gets to Go Home

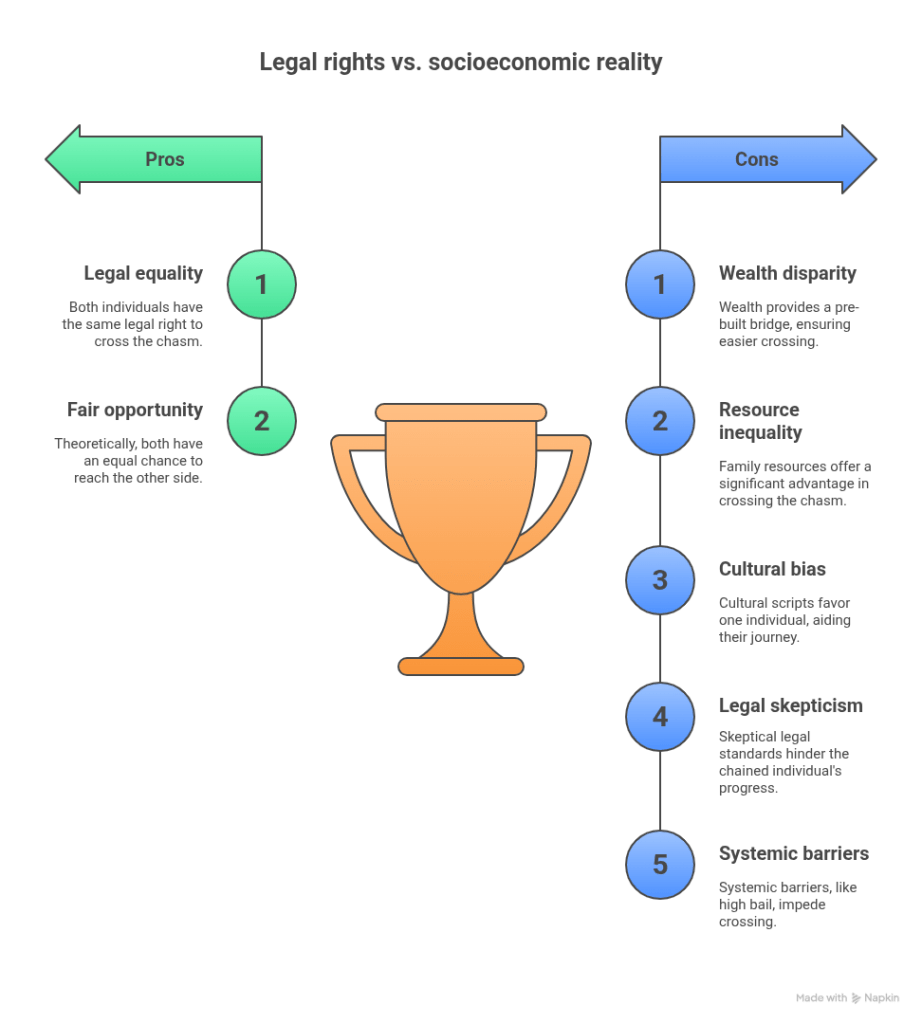

The contrast between these cases is clearest before trial, at bail.

Judge Andrew Peterson lowered Simonson’s bail from $300,000 to $250,000. After a family member posted bail, Simonson was released to home confinement at his parents’ Wasilla property with an ankle monitor and limited permission to leave.

In Fairbanks, a judge had set Hillyer’s bail far higher: a $1,000,000 appearance bond (10% cash) plus a $1,000,000 performance bond (100% cash), with strict third-party supervision, GPS and alcohol monitoring, no alcohol or weapons, tight travel limits, and no-contact orders. She was to remain in custody until monitoring was in place. She never bailed out and remains incarcerated.

The bail gap reflects a harsh economic reality. Simonson’s release was feasible with six-figure cash and family housing/support, while Hillyer’s required seven-figure money plus intensive state oversight. Hillyer’s terms effectively operated as preventive detention for someone without wealth.

A Violent Backdrop

Placed alongside the Fox Hollow case, Hillyer’s case raises a broader question: not whether Alaska law recognizes self-defense on paper, but whether Alaska courts and communities recognize it in practice, especially when the defendant is a woman alleging sexual assault, and when surviving the encounter risks becoming its own punishable act.

The Reasonableness Problem

These cases hinge on one question: what would a reasonable person have done? Alaska’s self-defense law is fact-driven and sometimes doesn’t require retreat, but fear alone isn’t enough. Evidence like video, forensics, and witnesses can make or break the claim. And the first decision comes before trial: who gets to go home. Bail, family property, and money for experts can shape the record and leverage early. The result is a system where reasonableness is not only a legal standard, but a gatekeeping tool.

Leave a comment