It was January 7, 2026, when I first saw videos, news commentaries, and social media feeds detailing the last moments of Renee Nicole Goods’ life unfold as an ICE officer shot her in broad daylight.

The next day, I stood outside the Immigration Office in Anchorage, Alaska, with five others, protest signs in hand. I kept my car running as the temperature hovered around -10, so anyone who needed to warm up could. We took the honks and thumbs-up along with the angry faces, people flipping us off as they drove by. One truck even slowed down just to yell at us to get jobs. We stayed there anyway, bundled against the cold, while a sundog kept watch, it’s bright colors dancing high in the Anchorage sky.

A few days later was the StandUP Alaska vigil in remembrance of Renee Nicole Good in front of the Loussac Library. It had warmed up to 3 degrees, and I stood behind a row of candles encased in frozen water holders. Projected onto the wall of the library “DO-GOOD” and “DE-ICE ALASKA” flickered as several community members spoke about their native corporations in business with ICE, calling on an action request to sign the petition and force a reckoning of humanity, the history of colonization and the harm done fresh in many minds because in Alaska, like other places where indigenous were decimated, the generation trauma left behind is a reality to this day.

I had only heard Keith Porter Jr’s name earlier that morning. Beyond the headlines, social media play by plays and coverage of the protest in Minneapolis. As I drank my coffee I read on the news I could stomach on my phone, a story that highlighted him being the first publicly reported case of an immigration officer killing a U.S. citizen under President Donald Trump.

No one mentioned Keith Porter Jr’s name that night, and I was left standing, looking at the crowd of maybe 100 people, wondering if anyone else had heard his name and knew of his murder. I did the cowardly thing and because I didn’t have the details I do now, I stayed silent. The fear of looking like a fool drowning out my voice of courage. I vowed, walking to my car, frozen hands balled up in my gloves, that I would learn about Keith Porter Jr. and say his name, someday.

While the news, social media videos and shares detailing Renee Nicole Good were at the top without me having to do a Google search, I had to dig for Keith Porter Jr’s coverage, which consisted mainly from local news channels in Los Angeles, Los Angeles Daily News and Facebook posts from friends and community members.

Outside of Los Angeles and outside of communities already tuned into state violence, Keith Porter Jr.’s name barely registered. For many, he was invisible unless you were already searching the web for him.

Renee Nicole Good’s wikipage reads like a history report; Keith Porter Jr’s is a blip on the Deaths, detentions and deportations of American citizens in the second Trump administration

Wikipage, three paragraphs long, and listed under Renee Good’s excerpt.

On December 31, 2025, late in the evening, Keith Porter Jr., 43, fired shots into the air to celebrate the New Year. An off-duty ICE agent who lived in the same apartment complex came outside, confronted him, and shot him. The agent was not arrested at the scene, and Keith’s family was left trying to make sense of how a celebration ended in a death that officials are still investigating.

Two thousand miles and one week later, on January 7, 2026, during a confrontation involving federal agents in Minneapolis, Renee Nicole Good, 37, was shot and killed by an ICE agent.

That officer was not arrested either.

Two U.S. citizens.

Two families forever changed.

Two fatal encounters involving ICE officers with witnesses, both sparking public demands for transparency and accountability.

But when Renee Good was killed, the details of her final moments spread fast.

Her name hit social media feeds immediately.

People shared videos, statements, and outrage, and not just in Minneapolis. A planned “Weekend of Action” saw crowds in major cities on both coasts, including New York City, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, and Seattle, with over 1,000 events, holding candlelight vigils and protests.

The kind of public recognition that forces officials to respond.

What I can’t shake, and before I fall asleep in bed, I go over and over, in my restless, sleepy mind, microphone in hand, I say what I didn’t know at the time of the StandUP Alaska vigil: What about Keith Porter Jr.?

Part of the answer is how black and brown people and communities are written about and covered by decades of media coverage.

Words matter, they inform the public on how to think of a topic.

Coverage matters, they inform the public who is worthy of being a topic.

And who gets to speak on what happened matters because it teaches the public whose pain is credible, whose truth is trusted, and whose life is treated as disposable.

A Black man holding a rifle gets introduced to the public through a familiar stereotype: dangerous.

Federal officials described the Porter shooting as a response to an “active shooter situation,” while neighbors and family said he was firing into the air, and the story stayed boxed in as a local controversy instead of a national alarm bell.

Federal officials described the Good shooting as a response to a “domestic terrorist”, something national news drew back on after public outcry.

With Renee Good, the story became national instantly and the debate centered on whether she was a threat, a protester, a bystander, or a target. Even when officials tried to paint her as dangerous, the public reaction exploded anyway.

Attention doesn’t just change the conversation. It changes the resources.

Renee Good’s verified GoFundMe rose to more than $1.5 million in two days before it was closed.

Keith Porter Jr. has two GoFundMe pages, one with around $303K and another created to support his daughters, around 78K, but the national megaphone never showed up for him the same way.

No celebrities wore pins with his name. The Golden Globes response centered on Renee Good “BE GOOD,” “ICE OUT” while Keith Porter Jr. stayed largely outside the national narrative.

So I’m asking what we’re all thinking, but don’t always say out loud:

Is it easier to dismiss Keith Porter Jr. because he was a black man?

Because he was a black man with a gun?

Our country has spent generations training the public to see black men as threats first, and fathers, sons, and human beings second?

This isn’t about ranking grief or who is deserving of outrage.

This is about recognition.

It should not take the death of a white woman for the public to notice a pattern that has already been killing people.

Keith Porter Jr. deserved the same humanity.

And our country could have been paying attention long before it became impossible to ignore.

How a government executes its laws and executes its citizens is telling of where we are headed.

This is what I mean by ‘Murdered White Woman Syndrome, the pattern where white women’s victimhood is treated as more urgent, more newsworthy, and more human.

And if you think this is just a national media problem, look at what happens here in Alaska when the victim isn’t white with a story the public is trained to mourn.

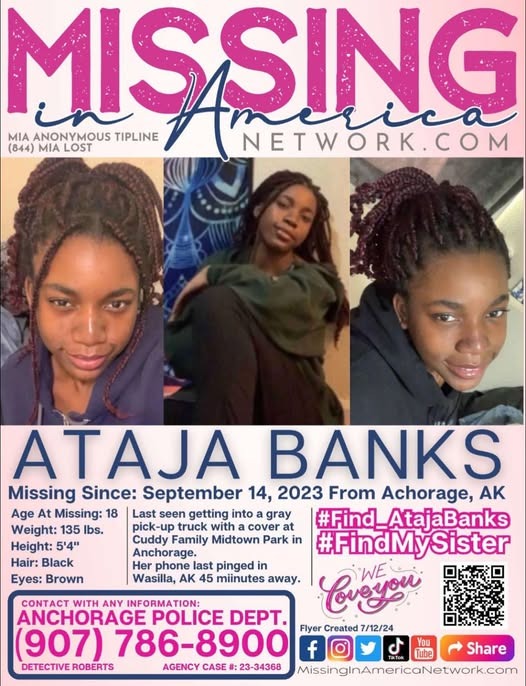

In November 2023, Ataja Banks was 18 when she went missing in Anchorage. Nearly two years later, her remains were found near Moose Meadows Road in Wasilla. Her disappearance didn’t become a national story. It didn’t flood the timeline. It didn’t trigger the same urgency that so often appears when the missing person is white, young, and easy for the public to “identify with.”

And she’s not alone.

Kenneyon Baker was only 16 when he was shot in front of his home in Anchorage on October 15, 2024.

Alena Toennis, 16, was found dead on a powerline trail in Wasilla in November 2024.

Aaron Jon Edwards Jr., 17, was found dead in a car parked at the intersection of 13th Avenue and Karluk Street in Anchorage on April 27, 2025.

Only one of these cases has been solved, Alena Toennis, and a suspect has been charged in both state and federal court. Alena mattered. Her death deserves full attention, compassion, and justice. This article is not about diminishing her. It’s about asking why that same urgency so often fails to show up when the victim is black or brown.

Ataja Banks was last seen getting into a gray pickup truck with a cover at Cuddy Family Park in midtown Anchorage. That wasn’t highlighted by media, but it was on her MISSING POSTER.

Kenneyon Baker’s family can’t get a call back from the detective and their lives have been upended by threats that the Anchorage Police Department has not investigated or followed up on.

Aaron Jon Edwards Jr. family shares “We do not have many details, and don’t have answers to any questions.” on their GOFUND ME.

So here’s the question many Alaskans don’t like to sit with.

Is it easier to dismiss missing people of color?

Because our country has spent generations training the public to see black and brown as threats first, and fathers and sons, mothers and daughters, as human beings, second?

News outlets and the media provide more coverage to cases involving white victims, especially young, conventionally attractive, middle-to-upper-class women. Media coverage sways public awareness, determining which issues the public thinks about, and how they think about them, a large part being the language and the images used.

Cases involving black and brown victims regularly receive less attention and are less likely to be humanized (photos with family are less common). Much of the time an unflattering ID or a less desirable booking photo is used.

If we only show up, write about, stand outside with a sign, or say their name when the victim is white, then outrage isn’t justice.

It is selected silence, shaped by narrative, reinforced by media, and used to decide whose life counts as worthy of public outrage.

Leave a comment